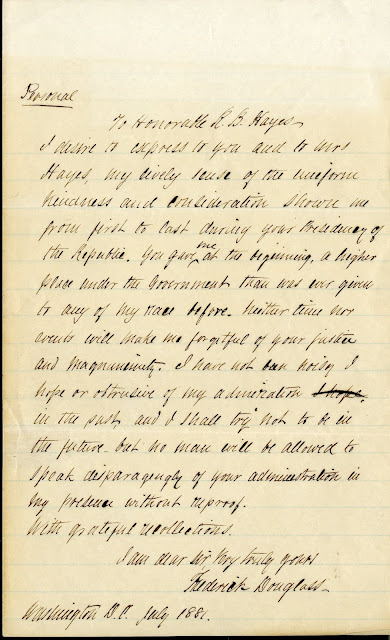

Some weeks after President Rutherford B. Hayes left

office, he received a letter marked “personal”. It began, “I express to you and

to Mrs. Hayes my lively sense of the uniform kindness and consideration shown

me from first to last during your Presidency of the Republic. You gave me at

the beginning a higher place under the Government than was ever given to my race

before. Neither time nor events will make me forgetful of your justice and

magnanimity…. No man will be allowed to speak disparagingly of your

administration in my presence without reproof.

With grateful recollections.” - signed Frederick Douglass.

Frederick Douglass Letter to President Hayes

Hayes Presidential Library and Museums

Learning that he was soon to be inaugurated as

President of the United States, Hayes consulted with Douglass and told him his

views regarding his Southern Policy. Douglass approved. Hayes recorded in his

diary that Douglass “had given him many useful hints regarding the subject.”

On March 17, 1877, in executive session, Hayes put

forth Douglass’ name as United States Marshal of the District of Columbia.

Senators overwhelmingly confirmed Hayes’ choice. It was to be the first of

several federal appointments, including Recorder of Deeds for D.C.; and

Minister Resident and Consul General to Haiti.

Frederick Douglass

Born into slavery in 1818 in Maryland and given the name Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, Douglass knew little of his mother and never learned the identity of his father. At the age of 8, his slave owner hired him out as a body servant in Baltimore where Douglass taught himself to read. Some 7 years later, the slave owner brought him back to the Eastern Shore to work in the fields. Douglass rebelled and physically fought back. He was returned to Baltimore where, disguised as a sailor, he hopped a train using money borrowed from a free black woman named Anna Murray, who later became his wife. It was then that they chose the surname of “Douglass.” Settling in Massachusetts, Douglass worked as an agent for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, where his fame grew as he spoke out against slavery throughout the North and Midwest. Fearing that he would be captured, Douglass fled to the United Kingdom where abolitionists purchased his freedom.

Once free, he returned to America and allied himself

with abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, helped people on the Underground Railroad, published the “North Star.” Two of his sons fought in the famed 54th

Massachusetts. Following the war, Douglass, now widely known and highly

respected, pressed for equal citizenship and voting rights. He later held positions at Howard University

and became president of the Freedman’s Bank.

Along with his duties as Marshal, Douglass brought

many of his friends and associates to meet the Hayeses. Among them were soprano

Madame Selika and Josiah Henson (believed to be the inspiration for Uncle Tom

in “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”) He attended Diplomatic Corps receptions and state

occasions. All the while he traveled and lectured on racial equality and

women’s rights. (And on several occasions, he spoke at Fremont, Ohio's Birchard Hall.)

Courtesy of Smithsonian

Learning of Lucy’s death in 1889, Douglass sent a letter to Hayes, expressing his heartfelt condolences. His home, Cedar Hill in Anacostia, is today a National Historic Site. It was here that Douglass died at age 77, after a life time spent in the fight for freedom and equal rights for all.

Frederick Douglass Home, Cedar Hill, Anacostia

Courtesy National Historic Sites